Manhattan jewelry designer and entrepreneur Sandy Baker is the owner and creative force behind Sandy Baker Art Collection. She claims she has been in the business for about 4,000 years, but it is probably closer to four decades. However, she has amassed such a huge amount of work, experiences, customers, and knowledge about the industry in that time that it would seem to be much longer than just four decades.

Her story is so different from all the other Influencer articles I have written. Sandy has broken countless barriers, from entering the jewelry world from a different direction than everyone else in the early ‘70s, to being one of a handful of women designers in jewelry at that time, to being the first African-American female to head her own jewelry company. And she has done it all with flash, finesse, panache, charisma and a uniquely Sandy-Baker style.

sandy7Sandy’s story began as she was destroying an oak table in her bedroom in Brooklyn. She had been teaching herself how to make jewelry on the table, and it is what prompted her to seek more professional and safe surroundings at the former West Side YMCA on 53rd and 7th. She started taking classes there instead of making jewelry in her bedroom. She raised a silver bowl that she still has, as well as some silverware. “It taught me that I didn’t want to be a jeweler by raising pieces,” she says. “The banging was hard on my ears and arms.” It also taught her how metal moved. She looked around and started taking classes wherever she could.

sandy7Sandy’s story began as she was destroying an oak table in her bedroom in Brooklyn. She had been teaching herself how to make jewelry on the table, and it is what prompted her to seek more professional and safe surroundings at the former West Side YMCA on 53rd and 7th. She started taking classes there instead of making jewelry in her bedroom. She raised a silver bowl that she still has, as well as some silverware. “It taught me that I didn’t want to be a jeweler by raising pieces,” she says. “The banging was hard on my ears and arms.” It also taught her how metal moved. She looked around and started taking classes wherever she could.

The classes at the YMCA helped Sandy decide to pursue a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree at Hunter College, where she had the life-altering opportunity to have Doris Kennedy as her teacher/adviser for three of her four years at the college. After Hunter, she explored a variety of design venues. She found that she wanted to wear jewelry that reflected who she was. She couldn’t find it, and so she began seriously making her own.

“I worked in a boutique in Harlem while going to school,” she says. “One day an African gentlemen came in who sold African artifacts. It was long before all the vendors you see now on the streets. He was going to do a trade show at the NY Gift Show and was looking for someone to work with him, but he couldn’t afford to pay them. I didn’t know what a trade show was, so I asked if I could show some of my jewelry (which I was selling in the boutique) and help him in his booth. He agreed. I don’t know how many African-American vendors were at the shows in 1972. I didn’t even know what a trade show was. I felt it would be an interesting experience and allow me to present my work to a larger audience. At that time the show was held at the NY Coliseum, now the Time Warner Center. Overflow was at a Sheraton Center hotel. After set-up, this trader and I were the only two people of color working the floor. I discovered a whole new world. Multi-cultural people from all over the world were there, just no black people except for the two of us. That is how I got my first clients. I wrote orders at the show! I started out at the Gift Show and then the Boutique show, not at Rhinebeck where virtually everyone else started.”

In 1977 Sandy applied to the Jewelers of America show and was interviewed by Mort Abelson, who was pulling together jewelers for the first Designer Section at a JA trade show. Most of them were from the Rhinebeck Craft Show. Sandy was the exception. She told Mort she had only done trade shows, and he told her she would have to have more gold as fine jewelry stores shopped this show. She agreed and was accepted. It forever changed her vision of what the jewelry world was about.

The Designer Section the first year was at the end of a hall on a balcony overlooking a main selling hall. The only people who found it were looking for the snack bar at the far end of the narrow exhibition space. The next year they invited more designers and moved them to the main ballroom. It was the beginning of a movement. But even though they were now a real part of the show, there was still some prejudice against designers. Many retailers had not seen work like theirs before. It was not traditional.

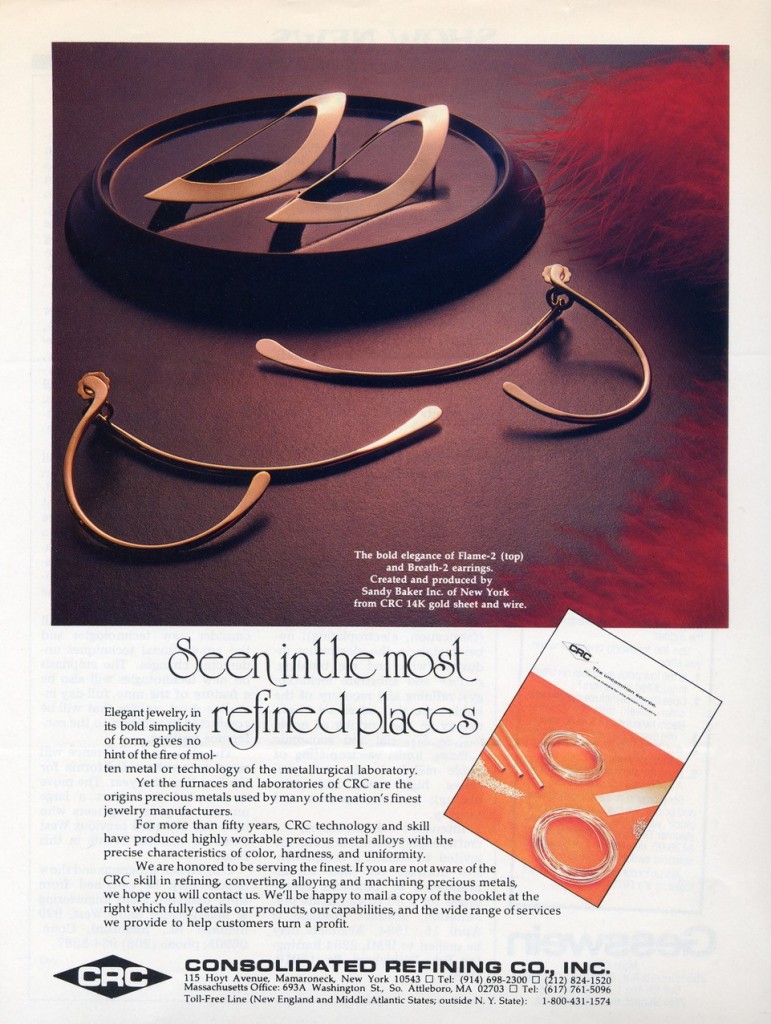

“At that point I was working mostly with hammered sheet gold and silver,” says Sandy. This was my first contribution to the jewelry world. The hammered metal caught the light differently than other pieces. I really liked the texture. Nothing was ever flat. At first it was called primitive. When I started doing it in gold, that was when people really noticed it. Then manufacturers in Providence started making tool and dies trying to copy the texture. It was becoming popular.” She tried casting some of her designs but didn’t like the weight. They were too heavy.

Since then Sandy’s customers have included Saks, Bloomingdales, I. Magnins, Fortunoff, Gimbels, B Altman, Abraham & Straus, and a host fine jewelry stores nationwide. Today, she still makes her own jewelry, which is sold in fine art galleries and museum gift shops around the country.

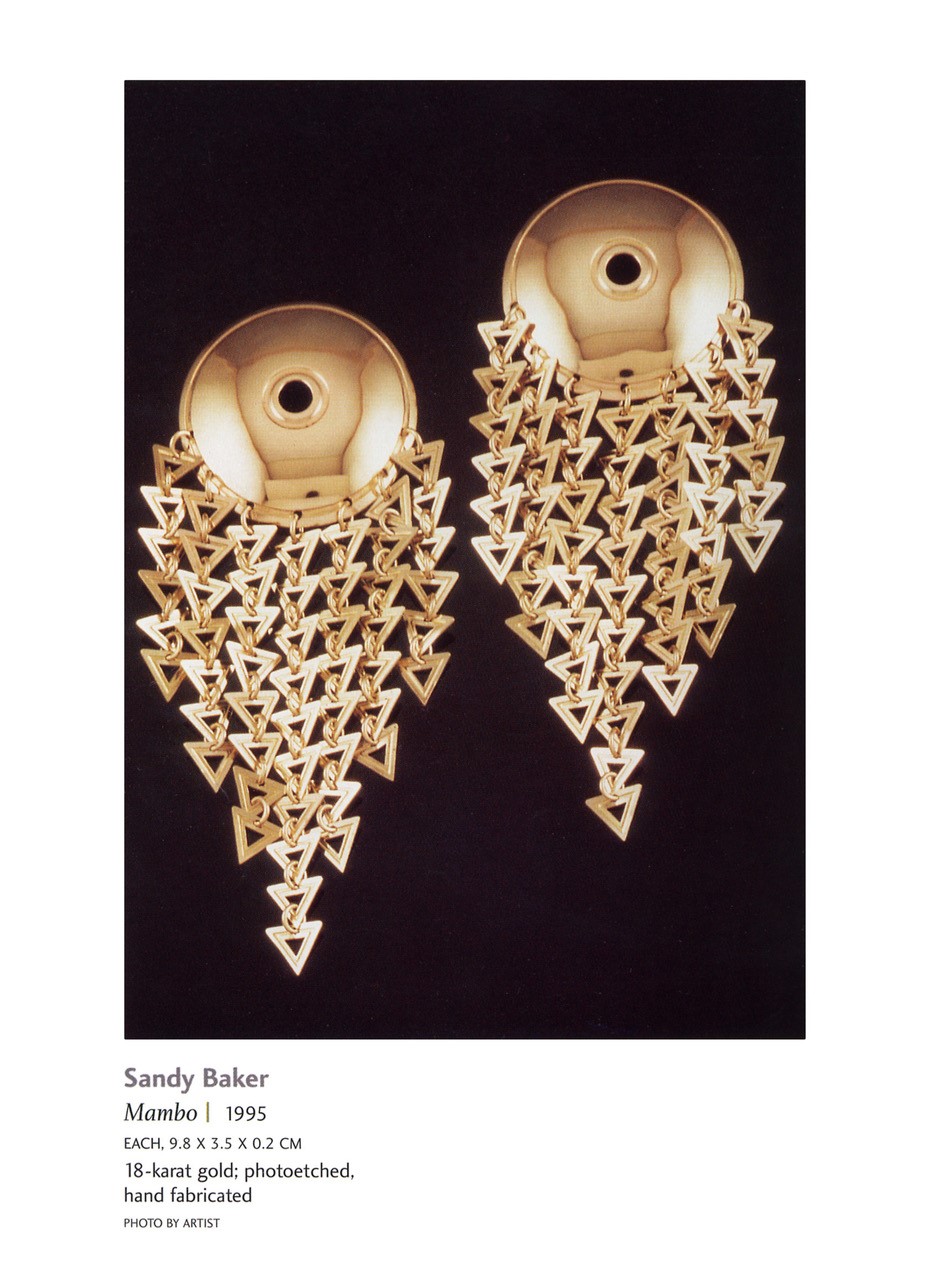

Sandy credits some of her success to being what she calls the queen of accurate volume.

“Many of the pieces I create have their own momentum, like fancily mobiles,” she says. “The breezy spaces between and around the actual metal is as important to the overall design as the elements themselves. I think in terms of line, shape and form. If there’s a curve, I want to highlight the way the light hits the bend. Dangling shapes, space and colors and textures all work together, like a design ballet.”

She also quickly found that she needed to hire people who could help her replicate her designs while staying true to the idea of a handcrafted piece. Often the people she turned to weren’t traditional jewelers.

“I hired people so we could replicate pieces,” she says. “I had skill tests for finding people who I wanted to work for me. The most important things were that they could follow instructions and accurately read a ruler. This was critical. My first two employees worked with me in Brooklyn and were with me for a very long time. They liked the freedom, especially when I got the results I wanted. I taught them to make jewelry from scratch. I purposely hired people who didn’t have jewelry backgrounds and taught them. My handcrafted jewelry really is handcrafted.”

“My inspiration has always come from the wonderful world around me,” she says. “Paying attention to the jewelry out there is essential. The strength of jewelry going forward will be good design. This is the key to survival.”

When Sandy is designing she keeps in mind at all times the women for whom she is designing. She doesn’t want the jewelry to overpower the wearer. She designs with a cameo focus—what does her jewelry look like on the upper body, neck and head? Jewelry should be a complementary accessory.

In her artist’s statement she says: “The design of each piece is approached as a work of sculptural art luxuriating in the use of three-dimensional space. The results are fluid graceful and timeless. When designing earrings I keep the contours of the face in mind: what I like to refer to as the ‘cameo focus’ because the face is the most noticed and appreciated part of a woman’s overall beauty.”

Sandy has witnessed so many changes in the jewelry design world and has been the catalyst for many of them. What an extraordinary legacy from an extraordinary lady!

Want to hear more inspirational stories from about jewelry designers?